The Invisible Graveyard of Rectums

Why haven't American radoncs been using rectal brachytherapy?

Over the last decade, organ-preserving treatments with definitive chemoradiation therapy for rectal cancer have become more prevalent. Approximately 60–70% of well-selected patients who undergo definitive treatment with chemoradiation, often incorporating total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) approaches, are able to be cured while retaining a preserved rectum. This treatment offers cure rates comparable to trimodality therapy while allowing patients to retain their rectum and its function. The data do not indicate any decrement in surgical outcomes. It is becoming a standard of care, particularly in patients with intermediate risk tumors.

In my experience, patients are often referred by the surgeon or medical oncologist for organ-preservation therapy, and that is the intent from the outset—rather than the patient saying, “I’m not going to go for any surgery,” which was more common before this data emerged. My practice is to inform them that tri-modality therapy remains the standard of care (with a TNT approach for most patients), but the outcomes of organ-preservation therapy appear promising, and surgery can still be used as a salvage option. If I sense that a patient is hesitant or unlikely to adhere to frequent examinations or proctoscopy, I advocate more strongly for surgical approaches.

Now, you may ask: what is the benefit of definitive, organ-preserving treatment for patients who are eligible for sphincter-sparing (LAR) approaches? This is not as simple as reattaching the bowel after removing the tumor via the TME technique. There are many other complications: LAR syndrome (fecal incontinence, urgency, frequency), sexual dysfunction and pain, chronic pelvic pain, general surgical morbidity, and anesthesia-related risks (as contact brachytherapy doesn’t require general anesthesia, just local). Avoiding these issues may help maintain quality of life. But, overall, patients don’t love surgery, they do like keeping their own rectum even if it is a little worse for wear and I have not had many patients showcasing decision regret.

One drawback of organ preservation is the misconception that bowel function will remain unaffected. This is not true—even without surgery, patients often experience gastrointestinal (GI), genitourinary (GU), and sexual dysfunction. However, on average, these effects appear less severe than those associated with trimodality therapy. Oncologic uncertainty remains, as strong evidence is lacking to confirm that organ preservation achieves equivalent cancer control to trimodality therapy with TNT. The primary endpoint, cCR, is somewhat subjective and requires serial examinations, endoscopy, and consistent patient adherence. Challenges in this process can delay the diagnosis of recurrence. Late salvage may result in poorer cancer outcomes and increased toxicity, as more complex surgery is often required. Long term outcomes had not until recently been published, but I will talk about that in a moment. There are psychosocial issues - like with prostate cancer - still having the tumor / organ inside the patient may have significant anxiety that there treatment is not really complete, that the tumor could come back and it could be worse. Finally, expertise in the best way to preserve the rectum is limited and that’s what I will spend the rest of the time discussing.

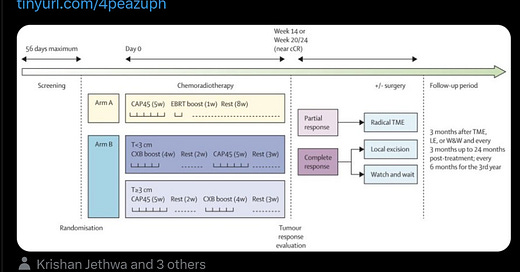

The OPERA (Organ Preservation in Early Rectal Adenocarcinoma) trial was a multicenter, phase III study that evaluated the efficacy of adding contact X-ray brachytherapy (CXB) to standard chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in patients with early-stage rectal adenocarcinoma. The primary goal was to assess whether this combination could enhance organ preservation rates.

Study Design:

Participants: Patients aged 18 or older with operable, biopsy-proven cT2-cT3b low-mid rectal adenocarcinoma, tumors less than 5 cm in diameter, and cN0 or cN1 status.

Intervention: All participants received external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) of 45 Gy in 25 fractions with concurrent capecitabine. They were then randomized into two groups:

Group A: Received an EBRT boost of 9 Gy in 5 fractions.

Group B: Received a CXB boost of 90 Gy in 3 fractions.

Key Findings:

Clinical Response (Weeks 14-24):

Group A: 65.7% achieved clinical complete or near-complete response.

Group B: 94.3% achieved clinical complete or near-complete response (p < 0.001).

3-Year Organ Preservation Rates:

Group A: 59%.

Group B: 81% (p = 0.003).

5-Year Organ Preservation Rates:

Group A: 56%.

Group B: 79% (p = 0.004).

Local Relapse at 5 Years:

Group A: 39%.

Group B: 17% (p = 0.1).

Distant Metastasis at 5 Years:

Group A: 14%.

Group B: 13% (not significant).

(above generated by ChatGPT; I checked and it is correct; I will always let you know when I do that)

Let’s be clear that this is a favorable group of patients T2-T3b, N0-N1 and that many patients in this group can be treated with surgery alone or surgery and chemotherapy without radiation therapy. However, the outcomes are excellent. The organ-preservation rate at 5 years is nearly 80%, an absolute improvement of over 20% compared to external beam boost approach. This is because of a >20% improvement in local control. It is notable that even with 54 Gy with chemotherapy the recurrence rate was nearly 40% at 5 years (vs 17%). In my opinion, these are stunning outcomes and represent a significant victory for organ preservation.

Now, some criticisms. One could argue these patients could have done better with a TNT approach, as many of them would have been candidates for that. With additional TNT, would brachytherapy have made as much of a difference. One could also argue that using contact brachytherapy instead of HDR makes this treatment inaccessible to many patients, particularly in the United States, where its use appears rare. In addition, contact brachytherapy does not allow high doses for thicker tumors (with 50kv x-rays, the 1cm dose is 10% and the 2cm depth dose is 1%) and so patients have to be well selected. Another criticism is that we can probably give more than 54 Gy with IMRT approaches and if the control rate is on the “shoulder” of the dose curve, perhaps going to 60 Gy would have mitigated the advantage of brachytherapy. I can’t think of much else I would criticize.

Dr. Nina Sanford had an excellent tweet-orial (X-torial?) on this very topic (click the picture to see the tweet!)

Nina’s key points: 1) These are small tumors - majority <5cm and T2 2) A subset of patients required local excision, but still considered as organ-preserved. When patients get LE, they are harder to surveil and future TME is more challenging 3) 63% had grade 1-2 bleeding 4) Why so little brachytherapy in the US?

The fourth question is what I want to delve into. Why are we not doing this more in America or studying it in phase II trials or getting the equipment/training to learn how to do contact therapy? I did a brief survey of GI radiation oncologists. I could only find one that does it and they use shielded HDR cylinders and deliver 1-2 fractions of 5 Gy each. Other than that, there are a few studies but very few patients are receiving this treatment or even having it discussed as an option.

Here are some considerations:

We don’t have prospective evidence for HDR and because we don’t have contact therapy, it is unclear if it will translate.

I do not see many American investigators publishing their experience with HDR, but international experience abounds (these are 3 separate articles, btw). This treatment appears to work quite well. The dose delivered is high and control rates are high. One of the study noted a pCR rate of 66% (these patients underwent surgery after CRT and brachytherapy) and that dwarfs what we seen from any other pre-operative approach. I am not a brachytherapy expert - in terms of both experience and knowledge. But, I am a board certified radiation oncologist. One can take this data and the results from OPERA and come up with a feasible HDR dose that can be used in an American clinic. We are quite “wedded” to the literature (think about people not offering hypofractionation to DCIS patients until there was an RCT or not using monotherapy HDR/LDR brachytherapy for unfavorable IR prostate patients, despite published institutional outcomes showing excellent outcomes). Our reliance on strict inclusion criteria often prevents patients from accessing treatments that improve cure rates, reduce toxicity, or maintain quality of life.

Brachytherapy is inconvenient and a time-suck for the clinic and the physician

This comes up often. Our schedules are blocked nearly a half day when doing brachytherapy and it become difficult to see other patients or work on administrative duties. The need for physician supervision makes it very challenging to do certain outpatient procedures, particularly those that work in free-standing centers. The clinic ends up “all hands on deck” and they are unable to perform their usual nursing and RTT duties, which either means clinic slows/stops or the need for more labor. This is all true, but it is also true that this is anti-patient. Cancer is inconvenient, our job is to provide the best care possible and if we are doing this because it is hard, that is not acceptable. We will need to work on better ways of allocating labor and resources if we desire to have the best outcomes for these patients.

Most of us are not trained well enough in brachytherapy in the United States

This is true. I don’t have any response to this other than: RESIDENTS - please take an interest in this. There are many reasons why the training has diminished and I may talk about this in another post. But this is definitely a factor. If people don’t have the experience in residency and hardly do it in practice, there will be no impetus to start doing it mid-career. I certainly am guilty of that - I tell future potential employers that I will not be doing any prostate brachytherapy. Our societies are raising awareness about this and trying to start programs to train more brachytherapists, but even if it works as advertised, there will be a long lag.

Discomfort with “butt-stuff”

Over and over, patients come into the ED with rectal bleeding and rectal pain and the note from the provider does not mention a rectal exam. Medoncs treat anal and rectal cancer patients, but do not do an exam. Patients are often resistant to allowing us to perform the procedure. Contra, we have been doing intra-cavitary brachytherapy for gynecologic malignancies since the dawn of time. As many of us know anecdotally, female patients are much more receptive to pelvic and rectal exams, as they have had them done for years before they saw the oncologist. Men act like you are about to violently torture them (okay, so that’s me). There is a collective discomfort with examining or inserting devices into the rectum. Physicians need to become more comfortable with this. It is literally saving people’s asses.

…

With the results of this trial, American radiation oncologists have to become more comfortable with these techniques. They need to better allocate resources to the department and the physicians involved. This approach will require high standards of care, pushing centers to develop expertise in accurate assessments and follow-up. Many patients will likely need to go to tertiary centers until this treatment is socialized. They will need to purchase new equipment, train abroad and ask for proctoring from experts. The solution lies in investing in training programs and equipment, supported by national organizations like ASTRO. Building CXB/HDR capacity aligns with the broader goal of personalized, patient-centric care, which must evolve with technological advancements. Clear communication about risks and benefits, alongside thorough psychosocial support, can mitigate decision regret. Most patients, when informed, prefer to avoid surgery if outcomes are comparable, as evidenced by real-world experiences and patient-reported satisfaction in studies like OPERA. Finally, we have to get over our discomfort with the rectum so we can save the rectum.

We simply cannot let a treatment that works incredibly well fall to the wayside because of external factors that have nothing to do with the patient and their cancer. I encourage ASTRO, ACRO and leading GI radiation oncologists to make this a priority in the coming years.

Love you all,

Sim