Diversity Math: Overrepresentation, Underrepresentation, and General Confusion

It's all fun and games until we actually look at the numbers

Improving diversity, equity and inclusiveness is a laudable goal. However, the academic publishing in this space has been dismal. “Counting” studies are especially pernicious as they do little but “raise awareness” and pad faculty and trainee CVs. The conclusions typically find that X group is underrepresented and “efforts should be made to improve their representations”. And then, the efforts are not made. The reasons for this are many, but in the case of a recent publication, the authors have run into a math problem that I’ll get into below. We really need to do a better job of finding solutions and high impact journals should not run pieces that do not move the needle. This also made me think about Indian-Americans in a way that I’ve talked about with others, but haven’t examined further in detail. I hope you enjoy. Feel free to comment or respond. Also, please do subscribe - there is a $0 option and that gets you everything I write.

There was an article in JAMA Network published last month about Asian-American representation in medicine. My guess is that the authors wanted to show that Asian-Americans are not a monolith. Although Asian-Americans in general may be overrepresented, certain subsets may not be. By subsets, they are breaking this down by nation - i.e. perhaps there may be overrepresentation of Indian-Americans, but there may be underrepresentation of Nepalese-Americans. I want to be clear from the beginning - this is playing games. If you slice and dice larger groups into smaller groups, you will eventually find that some subset is overrepresented and some are underrepresented. But, we will get into that later.

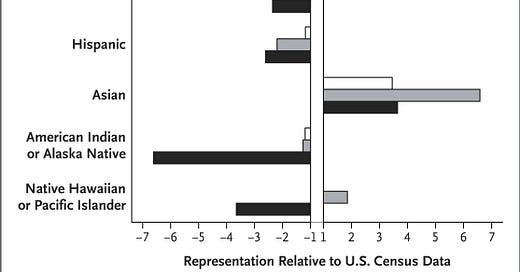

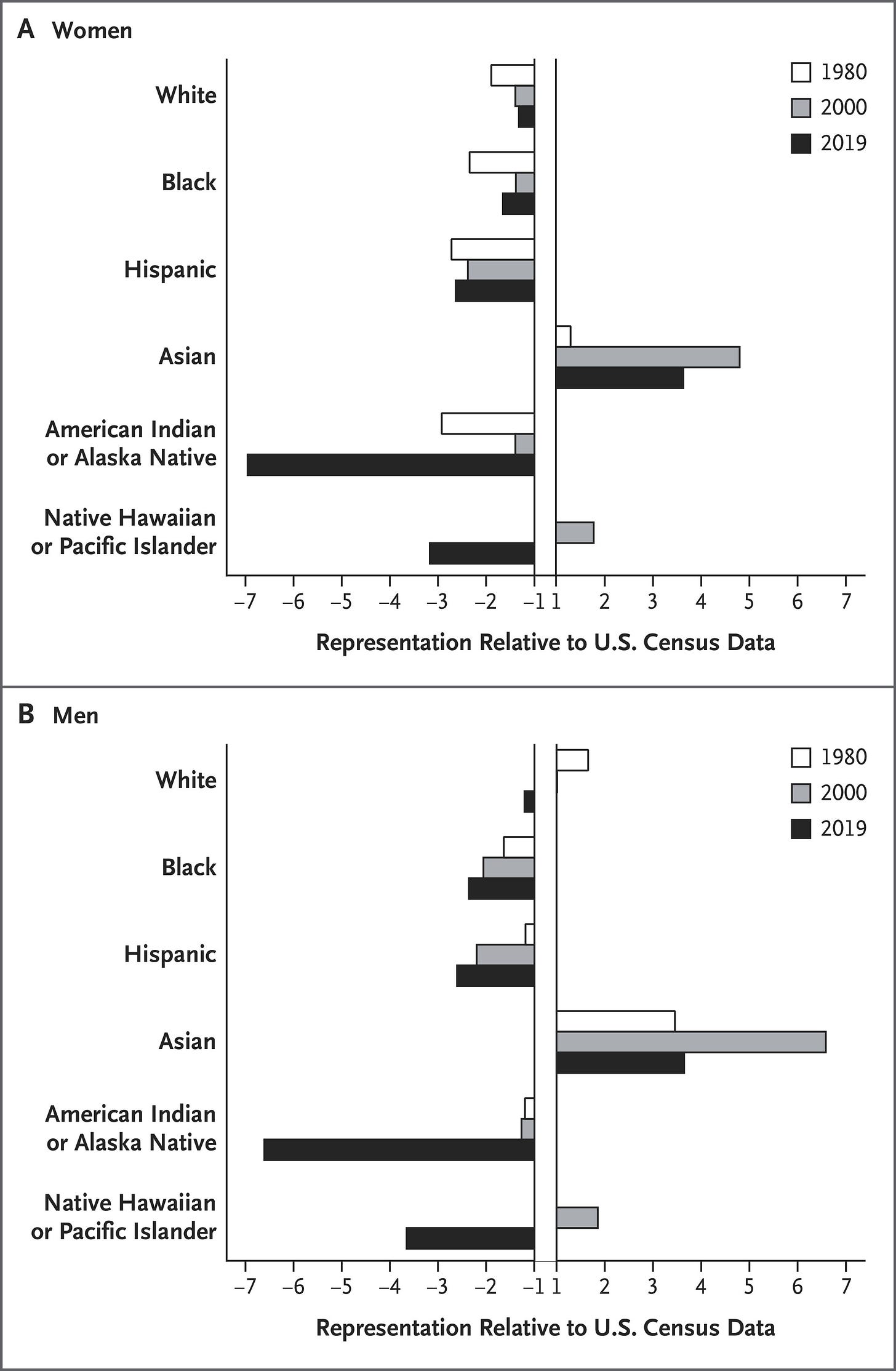

I want to quickly review a very detailed analysis of diversity of the American medical school population by looking at a chart from a paper in the NEJM.

This is a very revealing chart. We can see the relative proportion of the identity group in medicine as compared to the population as a whole. The closer the bar is to the midline, the more closely it represents society as a whole. From the DEI literature, the goal is to get as close to society as a whole, or perhaps over-represent those that have been marginalized in the past. As we can see from the chart, Asian Americans are heavily overrepresented, for both men and women. Native Americans are severely underrepresented. Black and Hispanic men and women are quite underrepresented, as well. White men and women are slightly underrepresented, but they are very close to the midline, so for the purposes of this post, let’s say they are correctly represented.

I want to relate a story. I was once in a virtual meeting with other radiation oncologists (before I ever saw this chart) about racial representation. I am Indian-American. I know we are the most overrepresented in American medicine and I don’t really need someone to disaggregate this and write a paper about it (please, dear readers, this is a pointless exercise, just trust me - we are). We make up about 1% of the American population and far greater than 1% of the entering medical school classes or practicing physicians (estimates range from 10-15%). On the call, they were talking about how to increase diversity. I said that the best way statistically to improve diversity is to convince Indian-Americans to not do medicine. It is is zero-sum game. If Indian-Americans are overrepresented by 1000% or more, then the simplest solution is to create a massive program to get more of us into other fields. Aziz Ansari or that one guy in No Doubt or Ro Khanna could be the champions of this program. “Considering medicine to make mom and dad happy? How about you tell them you’re going to move to LA and try standup? Yes, you may get disowned, but think about the service you are doing for America #diversity”. Everyone sort of got quiet after that and we finished the call. Some of the people on the call I considered friends, but I never heard back from them again.

To quote one of the 2000s leading philosophers, “Hi, it’s me, I’m the problem”. I may seem very cool and unique to you all, but here’s the back story. Mom and Dad were Gujarati immigrants to Canada then the U.S. They were mid-level IT workers and created a nice upper middle class life, their peak earnings approached maybe $150-175k in the late 1990s-early 2000s. We were just well off to have a single family home, occasional vacations, but a layoff away from anxiety about paying the mortgage (my dad was laid off several times in the 2000s and 2010s). They saw that I had a pretty good engine for math and science. They pushed medicine as the best way for an immigrant to create a stable life and to generate wealth. I had no issue with going into medicine - it’s awesome, I love being a doctor. I had a moment in 2000 where I was considering education, instead. My mom and dad were not the “Do as we say!” Indian parents popularized by TV and, uh, reality. They said, “Simul, you have big dreams. You like to buy stuff and want to see the world. You said you want to help us in retirement and be generous and charitable. Being a high school teacher will make these dreams harder. But, if that’s what you want, of course we support you.” Fast forward and I’m in my fifteenth year of practicing medicine. My story is not unique. I bet most of us were pushed (with a soft touch or an aggressive shove) into medicine, had some doubts or reconsideration, but ended up as physicians and, as mom and dad promised, entered a stable career and started generating wealth.

Indian-Americans are becoming the wealthiest demographic group in America. There are many claims about why. One much discussed reason is that because they are restricted from the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program and so they come to study higher education here and then naturalize or arrive as highly educated professionals, then naturalize. That claim holds up for many of us. Due to chain migration, this is not always the case. I am pretty sure you know of many Patel families that work at Dunkin Donuts or Subways or motels. They started without degrees or family money and worked towards their American dream, while telling their kids: “You can be anything you want when you grow up, as long as it’s a doctor or an engineer. See how liberal we are? We aren’t even saying you have to be a cardiologist.” (Zarna Garg has a great bit on this, go see her in person, she is hilarious).

I don’t want to want to get into the weeds with the reasons for why Indians achieve stability and financial success, but I tend to agree with Tyler Cowen. He says this particular group excels at “cracking cultural codes”. It is worth a listen, but what he suggests is that the flexibility of Indian immigrants allow them to succeed in new environments. Within a year of being in America, my once vegetarian dad began to eat meat (“Hamburgers at the dining hall were so good and I could eat as many as I wanted!”. He wore bell bottoms and cool floral shirts and he smoked cigarettes and he even dated non-Indian women (guess I caught that bug, too). Although the majority of his friends were Indian immigrants like himself, he familiarized himself with American culture, sports, food, etc. so he could have conversations with the natives. He watched Three’s Company late at night to get better at English and to pick up slang (my mom still tells me how loudly he’d laugh when he finally got all the jokes). He was always a good cook, but he could make any type of cuisine. He was able to joke around with me and my sister’s non-Indian friends and talk politics with co-workers. Dad was pretty cool and looking back, I think of him as quintessentially American. He did well in America, took great care of his wife and kids and I owe pretty much everything to him.

Navigating American culture is a balancing act for immigrants. If you stay too close to your roots, you may have difficulty in breaking into the tightly knit social and professionally communities, using network effects and being able to find your way into the upper strata. But, if the pendulum swings too far the other way, you lose your connection to where you are from. You may no longer speak or understand your mother tongue. You may not make time for visits and your children may not even realize they have Indian (or other) roots. The phrase for this is “white-washing”. In modern America, particularly in progressive circles, the slur “white-adjacent” is being used. Please never say that about anyone. This is akin to the nasty comments about “Uncle Toms" or “acting white” that people may say to minorities that succeed. There is nothing wrong with immigrating to America and becoming American. Its the point.

Interestingly, even deeply assimilated Indian-Americans who watch hockey, marry non-Indians and have stopped eating spicy food (the nerve!) still tend to have a disproportionate amount of Indian friends. They may not go to the temple for religious services, but they attend several Diwali parties in the fall where their kids perform dances to the latest Bollywood songs. They may never visit India, but their kids go to the temple … for spelling bee camps. They are American in all ways externally, but still are deeply connected to their Indian roots. I find it to be a good balance and I think it does explain some of the success the group has had in America.

Okay, let’s get back to this article. This is not a radiation oncology article, but it may as well be, as more than half of the authors are in this specialty. And, of course, 37% of the authors are Indian-American. Let’s look at the results:

RESULTS In this study, Asian American individuals accounted for 94 934 of 385 775 applicants (23%), 39 849 of 158 468 matriculants (24%), 37 579 of 152 453 graduates (24%), 229 899 of 1 035 512 residents (22%), and 297 413 of 1 351 187 faculty members (26%). The mean (SD) RQ was significantly greater among Asian American residents (3.44 [0.15]) and faculty (3.54 [0.03]) compared with Asian applicants (3.3 [0.04]), matriculants (3.37 [0.03]), or graduates (3.31 [0.06]). Upon disaggregation, RQ was significantly lower among residents and faculty in 10 of 12 subgroups. Although subgroups, such as Taiwanese American, Indian American, and Chinese American, had RQs greater than 1 (eg, Chinese American graduates: mean [SD], RQ, 3.90 [0.21]), the RQs were less than 1 for Laotian, Cambodian, and Filipino American subgroups (eg, Filipino American graduates: mean [SD], RQ, 0.93 [0.06]) at almost every career stage. No significant RQ changes were observed over time for Laotian American and Cambodian American trainees, with a resident RQ of 0 in 8 of 25 and 4 of 25 specialties, respectively. Faculty RQ increased in 9 of 12 subgroups, but Cambodian American, Filipino American, Indonesian American, Laotian American, and Vietnamese American faculty (eg, Vietnamese American faculty: mean [SD], RQ, 0.59 [0.08]) had RQs less than 1.

Poorer sub-groups of an overall rich demographic group have worse outcomes. Did not need a study to see this, but fine.

Now, let’s have ChatGPT summarize the article:

Asian American Representation in Medicine: A Closer Look

A recent study reveals the hidden disparities in Asian American representation across medical career stages and specialties. While Asian Americans as a group are often considered overrepresented in medicine, disaggregated data paint a more complex picture:

Uneven Representation: East Asian subgroups (e.g., Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese Americans) are consistently overrepresented, while Southeast Asian subgroups (e.g., Laotian, Cambodian, and Filipino Americans) face significant underrepresentation at every career stage—from applicants to faculty.

Barriers to Advancement: Factors like economic hardship, limited access to resources, and historical marginalization contribute to the stark disparities faced by Southeast Asian communities. A “glass ceiling” effect also limits Asian Americans from advancing into leadership roles.

Specialty Disparities: While Asian Americans dominate selective fields like radiation oncology, Southeast Asian subgroups are underrepresented across nearly all specialties.

Structural Issues: Immigration policies and historical legacies shape these inequities, such as the funneling of Filipino Americans into nursing during U.S. colonial rule.

What Needs to Change? The study advocates for:

Disaggregated Data: Collect and report subgroup-specific data to highlight inequities.

Expanded URM Definitions: Recognize Southeast Asians as underrepresented in medicine (URM).

Targeted Support: Invest in mentorship, financial aid, and programs for first-generation, low-income students.

Holistic Admissions: Prioritize candidates with significant barriers to success.

By challenging the monolithic view of Asian Americans in medicine, this research underscores the need for equity-driven reforms to ensure all communities have a voice and opportunity in healthcare.

You should read the whole thing. They spent a lot of time doing something that will not help any of these groups. Why am I so definitive about this?

Well, let’s take a look at one of the underrepresented groups - Laotians. I am very familiar with Southeast Asia, as I have been to Thailand and Vietnam several times; I actually spent a week teaching Vietnamese radiation oncologists. I’ve read many books about their culture and history. More recently have done a deep-dive into the Vietnam War, which is a misnomer, because the American government tried to destroy not only Vietnam, but they took their bullets and machetes and death to Laos and Cambodia, as well. Our government killed about 60,000 people there, more than the number of American deaths. The country remains underdeveloped and poor, there are still American land mines hidden that blow up people. The GDP per capita is about $2000 USD. Their cuisine is magnificent - I’ve met Chef Seng several times and I encourage you to go to one of her restaurants in the DC area.

The lucky few Laotians that can make it abroad tend to have much better lives outside of Laos than within. In America, there are about 200,000 Laotians and they make up about 0.05% of the population. There are just shy of 100,000 American medical students in America (all 4 years combined). If they are proportionally represented in American medical schools, there would be about 50 of them. Not 50 per year. 50 total, about 12.5 per year. If there are even 15 per year in a medical school class, almost every medical school will have underrepresentation - there are nearly 200 medical schools in America. And, when you get to residency, there are about 50 specialties, so nearly every specialty will be underrepresented. If any medical school or residency has one Laotian amongst their ranks, they will have an overrepresentation of Laotians. This is statistically true, but also completely useless.

Even if we double or triple or quadruple the number, we are going to have statistics that continue to show underrepresentation. This is just how math works when you have small numbers of an identity groups and large numbers of medical schools and specialties. The only way to increase their representation in a meaningful way is to 1) Develop programs to increase immigration of Laotians to America 2) Tell Laotians already in America to have more babies 3) Convince them to go to medical school. Other than libertarians/liberal-tarians (like me!), the American public does not want to talk about taking in more immigrants right now. As far as natalism - well, this is a problem for all demographic groups (save for Orthodox Jews, Mormons and a few other communities). We can attempt incentivizing having children, but this has not worked as of yet in Korea or Hungary. Studies like this that simply “raise awareness” do nothing to fix whatever “problem” the investigators think they have identified.

When there is a fixed number of positions for medical students and a fixed number of positions for residency, to change the proportion to mimic the national population will require us to boost certain groups, while restricting others - i.e it is zero sum. One may think we haven’t tried this, but in fact, we have already been doing this for years. For similar statistics, Asian Americans will have a harder time being accepted to medical school than other minorities, accounting for similar GPAs/MCAT scores. I am not saying GPAs or MCATs should determine whether one should get admission - I don’t make the rules. But, it appears that for some groups, you have to attain very high scores (i.e. - GPA / MCAT is the main metric for acceptance), while for others it is of lesser importance. In any case, even this has not helped, because the sheer number of Indian-American (and to a lesser extent, Chinese-American) applicants overwhelm the number of applicants that are characterized as underrepresented. Unless the bar is set even higher for Indian-Americans, there will continue to be a large disparity. We cannot just keep moving the bar up to create equity.

So, this gets us to the real question at hand. Do we think it should be a goal to have the demographics of physicians to represent the demographics of society as a whole? There is a debate in that question, but the same debate could be had for many professions, including education, the arts, professional sports, construction, modeling. For this post, I am not going to wade into that debate. I will take the side that medical school should represent the demographics of American society. Here are some way we can increase diversity and have the medical student population reflect American demographics.

Strict quotas on Indian-Americans in medical school. We make up about 1% of the population, but are about 10% or more of the physician population. This would dramatically reduce the number of Indian-Americans in medicine and open up positions for underrepresented minorities. Quotas are not going to be legal, so it would have to be an unwritten quota. Harvard has basically the same percentage of Asians in their entering freshman undergraduate class every years. This is not a coincidence. Reducing to about 5% will create 5,000 positions for underrepresented communities.

Programs / propaganda to convince Indian-Americans (and possibly Chinese-Americans) to choose other careers. We can promote the arts/culture, law, writing, media, journalism, construction, pro sports and other careers as alternatives. There is a risk they may come to overrepresent in those fields (well, in like law or journalism, but probably not basketball) or they may feel restricted if they truly wanted to become a doctor. But, this is probably crucial as these applicants currently attain the higher scores on the current metrics we use. It is challenging to change what people want to do when they grow up, but its possible.

Increase the number of positions in medical school, but in a way that benefits particular identity groups. This would allow us to not depend on foreign physicians as much as we currently do (primarily from India and China) and can homegrow them. With recent Supreme Court rulings in place, we cannot do this legally or make it policy, but we can use surrogates such as family income and wealth as a proxy for underrepresented groups. This will also help White Americans, as they are underrepresented in medicine and generally the progressive community does not see this as a positive outcome, but it would help at least increase socioeconomic diversity in addition to racial diversity.

Change the metrics that we use for medical school and residency acceptance. If we think GPA / MCAT / board scores are not indicators of what makes a good physician, then pick other metrics. But, to make certain groups depend on them to get into medical school while others can get lower scores sets us up for failure, as these scores by group are public and create a narrative than “lesser qualified” people are taking positions from “more qualified” applicants. There is a risk that new metrics will also be “cracked” by those groups already succeeding, but for a short time, it may level the playing field. Some thoughts:

Writing samples can be weighted more heavily than test scores

Experience in customer service - waiting tables is akin to managing a busy ED

Having paid jobs rather than extra-curricular activities

Not having a parent as a physician boosting should boost an applicant

Parents not having college education should boost an applicant

Ignore pedigree and favor state-school applicants

Favor applicants that have attended community college for at least 1 year of their undergraduate experience.

Identify and spread cultural traits that appear influential in success. I don’t know how much this mattered, but Mom and Dad made me do math worksheets at home after school and on weekends. I wasn’t really allowed to go to friend’s houses during weeknights, but I was allowed to play outside all evening. Thursday nights, I went to my friend’s house and his dad taught me higher level math. We concentrate on STEM majors . We don’t really get divorced. My mom was a “Tiger Mom” and it helped me to succeed. I will not use all of her tactics with my kids, because some had deleterious effects on my confidence and self-esteem, but the ideas that did work, of course I want to try with my own - we do not throw the baby out with the bath water. There is substantial literature on what may work - introduce these concepts to people that may benefit from it. This is not to say one culture is right and others are wrong - this is to say let’s pick and choose attributes from all cultures that lead to success and happiness.

I am not even sure I agree that there is a significant problem with representation in medicine as compared to other professions. There are so many other professions where there are higher levels of under and overrepresentations that could be studied further and can be discussed. Yet, the academic consensus is that there is a problem in medicine. If this is the case, then we need to get past counting numbers of people and “raising awareness”. We should analyze this thoughtfully and actually look for solutions. I find these types of publications to be purely window dressing and CV building rather than a commitment to social justice.

In an ideal world, all of us should have the opportunity to attain the American dream. Let’s work on it together in a way that isn’t divisive and leads to positive outcomes, preferably while enjoying some sai oua, naem khao and khao niew.

Love you all,

Sim